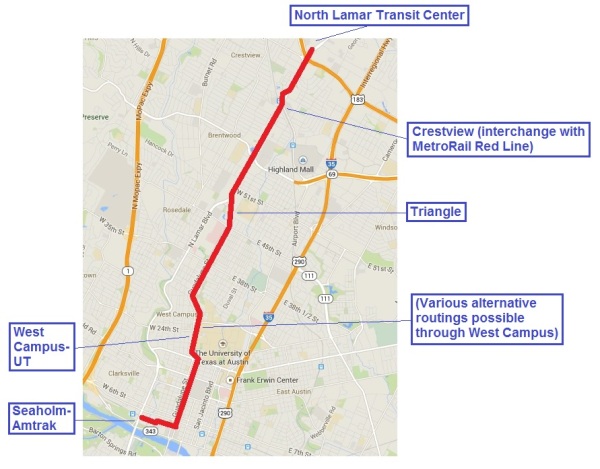

“Plan B” is a 6.8-mile light rail starter line route for Austin’s most central inner-city local corridor. It was originally proposed as a more feasible alternative to the official “urban rail” plan, defeated on Nov. 4th. Map graphic: Austin Rail Now.

♦

Austin, Texas — In a somewhat astonishing victory, on November 4th the city’s most dedicated, experienced, and knowledgeable rail transit advocates — including leaders of the Light Rail Now Project — helped defeat an officially sponsored rail transit plan that they said would waste resources on a very weak route and actually set back rail transit development in the community. See: Austin: With flawed “urban rail” plan now on ballot, debate heats up.

Produced by a consortium of several public agencies called Project Connect, the official plan — designated “urban rail” but in fact deploying light rail transit (LRT) technology — proposed a 9.5-mile route connecting the declining Highland Mall shopping center on the city’s north side (also a site being developed as a new Austin Community College campus) to the East Riverside corridor in the southeast. While the proposal was projected to have an investment cost of $1.4 billion in 2020, Austin’s City Council placed a $600 million General Obligation bond measure on the ballot as the local share, in hopes that the remainder would be covered by federal grants and other undisclosed sources.

It was that bond measure that was defeated, by a 14-point margin, 57%-43% — a stunning triumph for opponents, outspent 2-to-1 by a powerful coalition of the core of Austin’s business and predominantly Democratic political leadership, who also managed to enlist the support of major environmental, liberal, New Urbanist, and other “progressive” leaders. But a coalition of transit advocates and many other community and neighborhood activists otherwise inclined to support rail transit vehemently opposed the plan, objecting to what many perceived as a scheme that ignored crucial mobility needs in deference to real estate development interests. Many community members also felt excluded from what was depicted as a “fraudulent” process that had engendered the proposal. See: The fraudulent “study” behind the misguided Highland-Riverside urban rail plan.

For analyses of the campaign and defeat of the Highland-Riverside rail plan, see:

• Austin: Flawed urban rail plan defeated — Campaign for Guadalupe-Lamar light rail moves ahead

• Lessons of the Austin rail bond defeat

• Austin urban rail plan: Behind voters’ rejection

• Austin urban rail vote fails, alternative light rail plan proposed

With Austin’s most powerful business leadership, mass media, and Democratic Party-dominated political leadership arrayed against them, grassroots rail advocates, community activists, and neighborhood groups opposing the official “urban rail” proposition seemed to face overwhelming odds. Thus defeat of the official “urban rail” plan on Nov. 4th was an amazing upset. Graphic via TheKnowNothingNerd.com.

While the defeat of the City’s official plan might be seen as one step back, it could well lead to several steps forward in the form of a new “Plan B” LRT starter line in the central city’s heaviest-travel local corridor, potentially making far more sense to voters and attracting much broader support. This route, original proposed in the 1970s and intensively studied since the 1980s (and very narrowly defeated by less than 1% of voters in a 2000 regional referendum), follows the major arterials North Lamar and Guadalupe Street, serving increasing residential density and commercial activity in the corridor including the West Campus area adjacent to the University of Texas campus, with the third-highest residential density in Texas.

Various alternatives for a light rail starter line to serve this corridor are possible; one prominent example is a plan recently proposed by Austin Rail Now (ARN, a coalition of rail supporters including the Light Rail Now Project). As illustrated by the annotated map at the top of this post, this proposal envisions a 6.8-mile line, running from the North Lamar Transit Center (at U.S. 183) to the city’s Core Area (comprising the UT campus, Capitol Complex, and Central Business District). Along the way, it would provide a connection to the MetroRail diesel-multiple-unit-operated regional rail passenger service at the Crestview station (also a major development site), and important the Triangle multi-use development further south.

This plan also includes a branch stretching west to a new urban development site located at the former Seaholm electric power plant and current Amtrak intercity train station (at the western edge of the CBD). See: A “Plan B” proposal for a Guadalupe-Lamar alternative urban rail starter line.

With 17 stations and a fleet of 30 LRT railcars, ARN’s Plan B is designed to carry daily ridership of as many as 30,000 to 40,000 rider-trips — a figure derived from federally funded studies of the 2000 proposal, and roughly two to three times as much ridership as was likely for the now-defunct Highland-Riverside scheme. Yet, at a projected $586 million, and with no major civil works along the Guadalupe-Lamar corridor, it would have roughly half the investment cost, and an affordability likely to be more appealing to voters.

Furthermore, a cost-effective and financially doable starter line located in Austin’s centralmost and most heavily traveled inner-city local corridor could plausibly serve as the central axis or trunk of a far larger citywide LRT system, with lines branching into many other neighborhoods and outlying communities.

LRT in Austin’s North Lamar and Guadalupe corridor could resemble Portland’s Yellow Line on Interstate Avenue, shown here. Photo: Peter Ehrlich.

Supporters hope that this illustration of a Plan B LRT concept for Guadalupe-Lamar will provide a spark to re-kindle an official rail planning process that truly makes sense. Key to any plan for expansion of transit in Austin is acceptance of the need for re-allocating some street space — and traffic lanes — to dedicated transit use, and this policy is included in the proposal.

Most important, unlike the defeated urban rail proposal, a Plan B LRT on Guadalupe-Lamar seems to be an initiative that comes from the community itself. That’s an excellent ingredient for success. ■