It’s no secret that the Covid pandemic cast a pall upon public transport, and light rail transit (LRT) has certainly been no exception. But the good news, particularly in North America, is that, while ridership has taken a hit, major construction and enhancements have proceeded for many existing LRT operations.

Moreover, in recent years, even through the pandemic, totally new-start LRT projects for several North American cities (including in some metro areas already operating other forms of urban rail) have also been making progress. Light Rail Now reported briefly on several of these systems as they were under construction eight years ago.

At that time, the major new North American light rail system to open had been Norfolk’s <em>The Tide</em> rapid-type LRT in 2011. Now, since then, a swath of additional new systems have opened in the United States and Canada, and more projects are heading toward startup. Tabulated below is a quick rundown of these most recent new-start LRT projects, both “rapid” light rail and streetcar.

In this brief summary, all new rolling stock in the new streetcar lines described is modern except for heritage PCC cars in El Paso. In most cases, power to rolling stock is supplied by an overhead contact system (OCS, typically simple trolley wire or catenary), but some installations include battery operation as noted. Power is supplied at 750 VDC unless indicated otherwise.

LRT new starts: USA

► Salt Lake City: S-Line streetcar • Opened 2013 ► Using a former railway branch alignment, this 2.0-mi/3.2-km route connects the city’s Sugar House district with the nearby suburban community of South Salt Lake and links up with the region’s Trax rapid-type LRT system.

► Tucson: Sun Link streetcar • Opened 2014 ► Currently operating over a 3.9- mi/6.3-km route and powered by a standard OCS installation, the city’s streetcar-based urban rail system connects the University of Arizona campus with downtown Tucson and the Mercado District under development to the west.

► Atlanta: Atlanta streetcar • Opened 2014 ► This 2.7-mi/4.3-km line currently provides connections and pedestrian circulation services in a loop connecting Centennial Olympic Park with the Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historical Park and nearby neighborhoods east of downtown, including a direct link to the MARTA rapid transit system’s Peachtree Center station and other transit lines.

► Dallas: Dallas streetcar • Opened 2015 ► This 2.4-mi/3.9-km line modern streetcar line connects downtown Dallas to Oak Cliff, across the wide Trinity River flood plain, by way of the Houston Street Viaduct. An extension to the Bishop Arts District opened in 2016. Cars are mainly powered by OCS, but run on battery power over the viaduct. The modern system is totally separate from, and unconnected to, the heritage McKinney Avenue Streetcar line that has served its important neighborhood and commercial district since 1989.

► Charlotte: CityLynx streetcar • Opened 2015 ► Designated the Gold Line within Charlotte’s urban rail system, this 4.0-mi/6.4-km modern streetcar line initially opened over a mainly east-west route following Beatties Ford Road, Trade Street, and Central Avenue through central Charlotte. Additional links from the Charlotte Transportation Center to French Street, and from Hawthorne & 5th to Sunnyside Avenue opened for service in 2021.

► Washington: DC Streetcar • Opened 2016 ► Currently streetcar service operates over a 2.4-mi/3.9-km segment running in mixed traffic along H Street and Benning Road in the city’s Northeast quadrant.

► Kansas City: KC Streetcar • Opened 2016 ► Kansas City’s streetcar-based urban rail system follows a 2.2-mile/3.5 km route between the River Market and Union Station, mostly along Main Street, running through the city’s central business district and the Crossroads Arts District.

► Cincinnati: Cincinnati Bell Connector streetcar • Opened 2016 ► The service operates in mixed traffic on a 3.6-mi/5.8-km loop from The Banks, Great American Ball Park, and Smale Riverfront Park through downtown Cincinnati and north to Findlay Market at the northern edge of the historic Over-the-Rhine neighborhood.

► Detroit: QLine streetcar • Opened 2017 ► Originally called the M-1 Line by its developers, this 3.3-mi/5.3-km streetcar service connects Downtown Detroit with Midtown and New Center, running along Woodward Avenue for its entire route. Lithium batteries provide power in about 60% of the operating cycle, with OCS powering cars and recharging in the remainder.

► Milwaukee: The Hop streetcar • Opened 2018 ► Milwaukee’s Streetcar, branded as The Hop, provides a modern streetcar service over an initial 2.1 mi/3.4 km route connecting the Milwaukee Intermodal Station and Downtown to the city’s Lower East Side and historic Third Ward neighborhoods. A 0.4-mile/640-m Lakefront branch to the proposed “Couture” high-rise development has been mostly constructed, and is expected to open imminently. Power is supplied by OCS, mostly simple trolley wire, except for 3,300 feet (1 kilometer) in sections along Kilbourn Avenue and Jackson Street where cars are powered only by their batteries.

► Oklahoma City: OKC Streetcar • Opened 2018 ► This 4.8 mi/7.7 km system is routed over two lines that connect Oklahoma City’s Central Business District with the entertainment district, Bricktown, and the Midtown District. Most operation is powered under OCS except for two short segments where cars operate under battery power. (See photo at beginning of article.)

► El Paso: El Paso Streetcar (heritage) • Opened 2018 ►Using a fleet of renovated historic streetcars, this line runs 4.8 mi/7.7 km over two loops from through El Paso’s uptown and downtown areas to the University of Texas at El Paso. Notably, the historic PCC cars refurbished for the project had been kept in storage since the city’s last original streetcar operation was abandoned in 1974.

► Phoenix: Tempe Streetcar • Opened 2022 ► Serving Tempe, a large suburban city adjacent to Phoenix’s east side, this 3.4-mi/5.7-km modern streetcar line running in streets with mixed traffic connects the Arizona State University campus with downtown Tempe and neighborhoods to the south. It intersects several stations of the city’s rapid Valley Metro LRT system. Power for the streetcars varies between OCS and onboard batteries.

► Orange County, California: OC Streetcar • Opening planned 2023 ► This 4.2 mi/6.7 km modern streetcar (LRT) line is currently under construction in Orange County, California, running through the cities of Santa Ana and Garden Grove, routed partly in mixed traffic and in dedicated right-of-way. New infrastructure includes constructing a new double-track rail bridge and an overpass over a busy arterial.

► Washington DC (Maryland suburbs): Purple Line LRT • Opening planned 2026 ► This 16.2-mile (26.1 km) rapid LRT line is intended to link several Maryland suburbs of Washington, D.C.: Bethesda, Silver Spring, College Park, and New Carrollton. The line will also enable riders to transfer between the Maryland branches of the Red, Green, Yellow, and Orange lines of the Washington Metro without riding into central Washington, and between all three lines of the MARC regional (commuter) rail system. Power, likely to be delivered by OCS in a catenary suspension, will be energized at 1,500 volts (placing the Purple Line in a small category of new higher-power North American LRT systems that also includes Seattle’s Link and Ottawa’s Confederation Line).

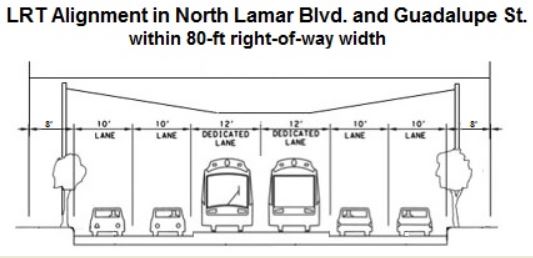

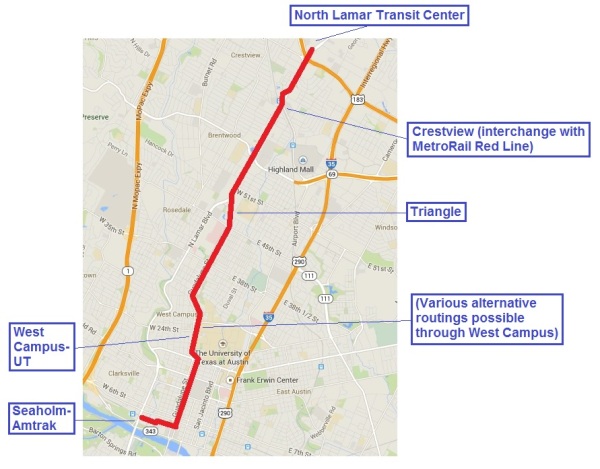

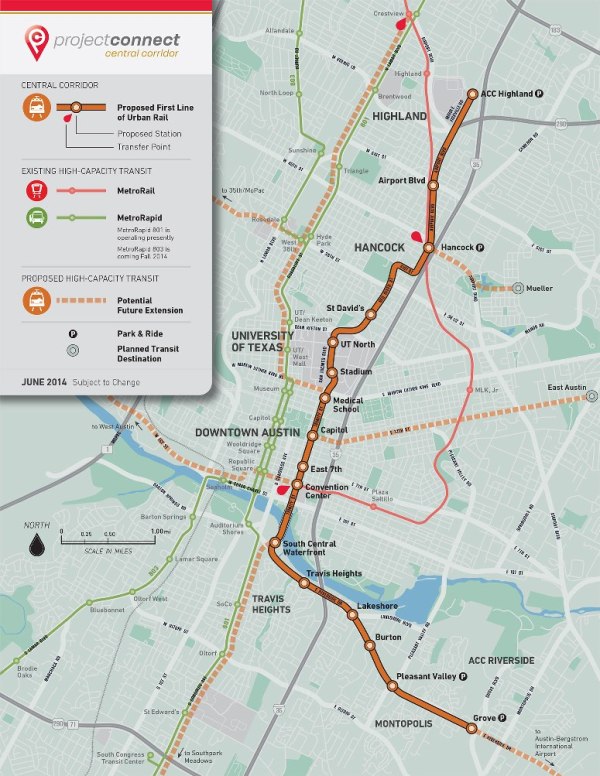

► Austin: MetroRail LRT • Opening planned 2029 ► Public transit agency Project Connect is planning two light rail lines, designed to operate free from traffic to link key destinations throughout Austin. The Orange Line, serving Austin’s crucial central north-south local travel corridor, is planned to stretch approximately 21 miles (34 km) to link North and South Austin. From Tech Ridge in the north, the line would follow North Lamar Blvd. and Guadalupe St., connecting the University of Texas campus, dense West Campus neighborhood, the Capitol Complex (state government offices), and downtown before crossing the Colorado River and heading south along South Congress Ave. to Slaughter Ln. in the far south of the city. The Blue Line would provide service over a 15-mile (24-km) route starting at U.S. 183 in North Austin, sharing the Orange Line alignment into downtown, then crossing the river and proceeding southeast to Austin-Bergstrom International Airport. Included in the original plan is 1.6-miles (2.6 km) of LRT tunnel as alignments through downtown for both Orange and Blue lines as well as a future eastside Gold LRT line.

LRT new starts: Canada

► Waterloo Region (Ontario): ION Light Rail • Opened 2019 ► The Waterloo Region is a cluster of urban villages about 55 miles southwest of Toronto. The 11.8-mi/19.0 km first stage of the planned larger ION LRT system, basically an interurban LRT service, connects Conestoga Station in Waterloo to Fairway Station in Kitchener, including 19 stations, some of them designed to serve trains in each direction on a single track. A particularly interesting technical feature is track-sharing with heavy freight railroads and the used of interlaced (“gauntlet”) track to facilitate operation through switches and clearances at stations.

► Ottawa: Confederation Line LRT • Opened 2019 ► The Confederation Line (Line 1) represents Ottawa’s first deployment of actual LRT technology, and replaces a section of the Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) Transitway that previously served the city center. (See photo at beginning of article.) This new line, completely grade-separated, runs both underground and on the surface 7.8 mi/12.5 km east–west from Blair to Tunney’s Pasture, connecting to the Transitway at each end and with the Trillium rail service at Bayview. It includes a tunnel through downtown with three subway stations. Electrification is relatively high at 1,500 VDC, delivered to trains by catenary-type OCS (similar to the power system used by Seattle’s Link LRT). It must be noted that the diesel-powered Trillium line, described locally as “light rail”, is technologically equivalent to other light-capacity regional diesel-multiple-unit (DMU) services (lately called “hybrid rail” by the U.S. Federal Transit Administration) such as those in New Jersey (River Line), Southern California (Sprinter), and Austin (MetroRail Red Line).

► Peel Region (Ontario): Hurontario LRT • Opening planned 2024 ► The Peel Region is a regional municipality of the Greater Toronto Area, just to the west and northwest of the city of Toronto, encompassing the suburban cities of Mississauga and Brampton, among other smaller communities. The Hurontario LRT, currently under construction, is a 10.9 mi/17.6-km light rail line planned to run on the surface along Hurontario Street from the Port Credit GO Station in Mississauga to Steeles Avenue in Brampton.

► Quebec City: Quebec City Tramway • Opening planned 2026 ► This light rail transit line in Quebec City is planned to open in 2026. The initial 14-mi/23-km route will link Charlesbourg to Cap Rouge, passing through Quebec Parliament Hill. While the line will include a 2.2-mi/3.5-km underground segment, most of it will be constructed on the surface.

► Hamilton: Hamilton LRT • Opening date TBD ► Hamilton is a large industrial and port city about 28 miles/45 kilometers southwest of Toronto in the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area. The Hamilton LRT (also known as the B-Line) is planned to operate along Main Street, King Street, and Queenston Road, extending 8.7 miles (14 kilometers), with 17 station-stops, from McMaster University to Eastgate Square via downtown Hamilton.

It should be noted that a 26-km (16-mi) starter line for a major LRT system has also been proposed for the city of Gatineau, Quebec, located on the northern bank of the Ottawa River, immediately across from Ottawa, Ontario within Canada’s National Capital Region. However, funding has not yet been finalized.

Considerations for other cities

This vigorous bustle of totally new light rail starts in nearly two dozen cities across North America is breathtaking – 21 new LRT installation projects (both rapid LRT and streetcar) in eight years. That’s not counting all the new extension projects of existing systems in cities like Seattle, Minneapolis, Milwaukee, Charlotte, Los Angeles, Phoenix, Edmonton, Calgary, and more.

The explosive growth of new LRT starts suggests that community members and civic leaders across the continent are increasingly recognizing the unique advantages of LRT for their cities – its exceptional attractiveness as public transport, and its powerful ability to catalyze and attract adjacent real estate development. This has simultaneously improved urban mobility, improved environmental quality, helped guide land use with techniques such as transit-oriented development (TOD), and boosted local taxbase with significant returns on investment (ROI).

Across North America, cities of various sizes remain that have no urban rail. San Antonio, Las Vegas, Indianapolis, Louisville, Omaha, Des Moines, Boise, Spokane, Knoxville, Raleigh, Richmond, Providence, Victoria, and Winnipeg are just a handful of the dozens of communities that would likely benefit from considering some form and application of light rail. The new starts that this article has summarized certainly provide some models to examine. ■

Reference sources

Light rail in the United States, Wikipedia, updated 7 November 2022.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Light_rail_in_the_United_States

List of North American light rail systems by ridership, Wikipedia, 22 November 2022.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_North_American_light_rail_systems_by_ridership

Urban rail transit in Canada, Wikipedia, updated 11 November 2022.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Urban_rail_transit_in_Canada

Dallas Streetcar, Wikipedia, updated 7 October 2022.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dallas_Streetcar

CityLYNX Gold Line Streetcar, City of Charlotte website, accessed 29 November 2022.

https://charlottenc.gov/cats/rail/cityLYNX/Pages/default.aspx

CityLynx Gold Line, Wikipedia, updated 29 October 2022.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/CityLynx_Gold_Line

DC Streetcar, Wikipedia, updated 24 October 2022.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/DC_Streetcar

Editorial, A new streetcar in Arizona: Tempe! Urban Transport Magazine webpage, 20 May 2022.

https://www.urban-transport-magazine.com/en/a-new-streetcar-in-arizona-tempe/

Tempe Streetcar, Wikipedia, updated 27 October 2022.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tempe_Streetcar

Tempe Streetcar, Valley Metro website, accessed 2022-11-28.

https://www.valleymetro.org/project/tempe-streetcar

Tempe Streetcar, Stacy and Witbeck website, accessed 2022-11-28.

https://www.stacywitbeck.com/projects/tempe-streetcar/

El Paso Streetcar, Wikipedia, updated 19 August 2022.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/El_Paso_Streetcar

The Hop (streetcar), Wikipedia, updated 25 November 2022.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Hop_(streetcar)

KC Streetcar, Wikipedia, updated 26 November 2022.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/KC_Streetcar

QLine, Wikipedia, updated 28 November 2022.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/QLine

About the Oklahoma City Streetcar, Oklahoma City Streetcar website, accessed 30 November 2022

Oklahoma City Streetcar, Wikipedia, updated 19 August 2022

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oklahoma_City_Streetcar

OC Streetcar, Wikipedia, updated 2 November 2022.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/OC_Streetcar

Light Rail Overview, Purple Line website, Maryland Transit Commission, accessed 29 November 2022.

https://www.purplelinemd.com/about-the-project/overview

Purple Line (Maryland), Wikipedia, updated 29 November 2022.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Purple_Line_(Maryland)

Project Connect Transit Plan, HDR website, accessed 29 November 2022.

https://www.hdrinc.com/portfolio/project-connect-transit-plan

Project Connect, Wikipedia, updated 4 September 2022.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Project_Connect

Stage 2 ION light-rail project receives provincial clearance, Mass Transit online, June 22, 2021

Confederation Line, Wikipedia, 27 November 2022.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Confederation_Line

Quebec City Tramway, Wikipedia, updated 3 October 2022.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quebec_City_Tramway

Quebec City tramway finally gets green light as province gives unconditional approval, CBC News, 6 April 2022.

https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/tramway-quebec-city-approved-1.6410943

Regional Municipality of Peel, Wikipedia, 30 September 2022.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Regional_Municipality_of_Peel

Desmond Brown, Procurement process for LRT to start later this year, construction in 2024, [Hamilton] CBC News, 18 July 2022.

https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/hamilton/hamilton-lrt-project-1.6524030

Hamilton LRT, Wikipedia, updated 28 September 2022.